After two world wars, men sought new outlets for their primal instincts. For Britain’s working-class youth, football became the new battleground—a theatre for fashion, fists, and identity.

British football fashion is a story of tribal belonging, with each movement on the terraces redefining what it means to stand out while staying part of the pack.

In this article, we’ll trace the history of yob couture, where football style has been more than just a declaration of team loyalty. From the glam rock flamboyance of the 1970s and the anti-establishment attitude of the skinhead movement to the polished swagger of casuals and the faceless rebellion of black bloc, British football fashion mirrors the political and cultural upheavals of its time.

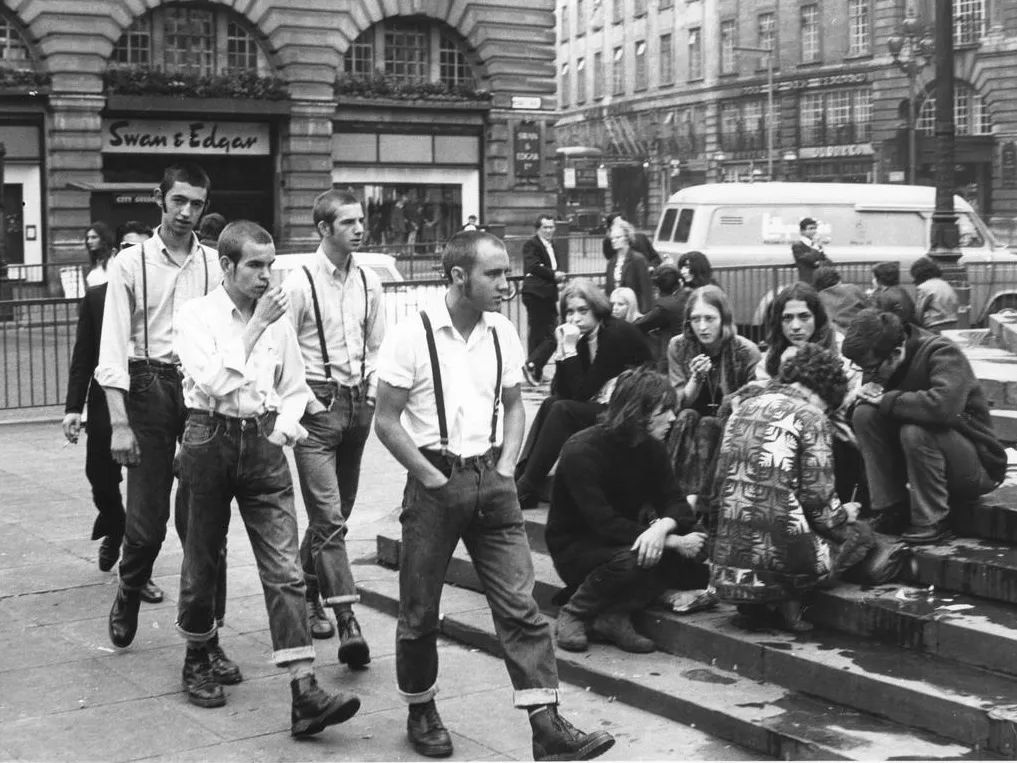

Bootboys and skinheads - the original hooligans

The original British skinheads of the late 1960s and early 1970s mark page one of hooligan history. While rowdiness had been part of football culture since the Football Association’s formation a century earlier, the bootboys and bovver boys of 1960s Britain were the first identifiable movement to blend hooliganism with a distinct, defiant style.

In a deliberate rejection of the freewheeling hippiedom of the sixties—with its bourgeois sensibilities and kaleidoscopic fabrics—football fashion pared back to working-class essentials. The mods of the 1960s had splintered into two camps: the long-haired psychedelics and the hard mods, the latter giving rise to the skinhead movement.

Skinhead style was puritanical, almost ascetic. Dockers, not dandies, they favored close-cropped hair, formerly associated with the military or prison, steel-toe boots (most famously Doc Martens), Crombie overcoats, Harrington jackets, half-mast jeans or Sta-Prest trousers, braces, and button-down shirts. It was the workwear aesthetic of its time—sharp but practical, functional yet full of intent.

This no-nonsense “back to basics” ethos was an embodiment of pride in working-class identity, toughness, and defiance. It remains a look unmatched in its ability to instill that ethos.

Richard Allen | Skinhead Chronicler

No exploration of the late 1960s and early 1970s skinhead movement is complete without mention of Richard Allen, the pseudonymous author whose pulp novels became cult classics among British youth. Titles like Skinhead (1970), Suedehead (1971), and Boot Boys (1972) delved into the raw, unvarnished lives of working-class youth—characters navigating a world of football terraces, backstreet brawls, and tribal loyalties. Allen’s work resonated with young readers, portraying skinheads not just as violent hooligans but as anti-heroes rebelling against a society they saw as hostile and hypocritical. Although often criticized for their sensationalism, they remain an enduring snapshot of the original skinheads.

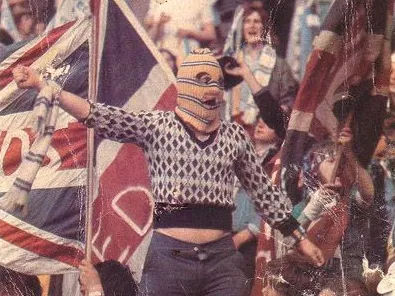

Glitter stomp

The terraces of the early to mid-1970s were a cacophony of clashing patterns, unkempt hair, and bell-bottomed bravado. Football during this period mirrored the chaotic, freewheeling energy of glam rock Britain.

In terms of a unified football fashion aesthetic, this era was something of a wilderness—an untamed, transitional phase where tribalism lacked the sharp focus it would later regain. Style was experimental but not yet refined, more chaos than cohesion.

As the skinhead movement softened into suedehead and later smoothie subcultures, fashion began cross-pollinating with the flamboyance of glam rock. Sharpness met flair. Suedeheads grew their hair a little longer and traded their rigid half-mast trousers for flowing Oxford bags. Across the terraces, Bay City Rollers-inspired tartan scarves tied tightly around wrists became as ubiquitous as the club colours. The shadow of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange loomed large, as did the influence of the Northern Irish Troubles, introducing en element of menace into the terraces.

Lads with flowing locks, sweeping Oxford bags, and platform shoes brought an unmistakable glam rock swagger to match day. Glam stomper bands like Slade, Sweet, and The Glitter Band fueled this flamboyant transformation. Yet, this was more than simple mimicry; it was rebellion through exaggeration, a refusal to go unnoticed. One might see echoes of Jean-Paul Sartre’s concept of bad faith: the paradox of expressing individuality while conforming to a role. But Sartre would have been laughed off the terraces. For football fans, the crazy trousers and wrist-bound scarves were less philosophy and more a wink across the pub: you belonged to the tribe, but on your own terms.

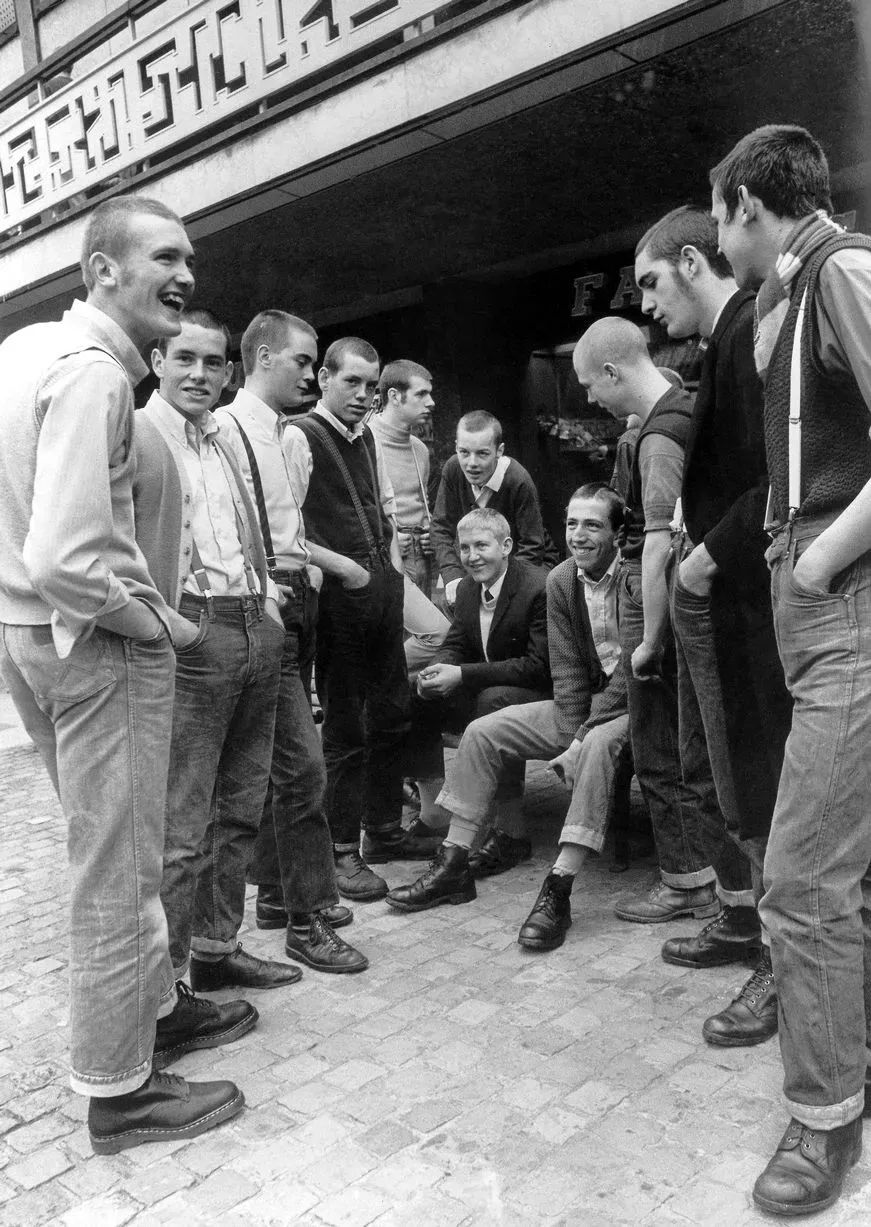

Oi! for England

As the 1970s drew to a close, the terraces underwent a stark transformation. The flamboyance of flowing locks and Oxford bags gave way to the brutal simplicity of shaved heads, Doc Martens, and braces. The football fan was no longer a peacock strutting in technicolour excess; now, he resembled a soldier on the front line. This was the era of the skinhead revival, where stark, aggressive aesthetics marked a sharp cultural shift in British football fashion.

These weren’t the reggae-loving, Jamaican-influenced skins of the 60s. The search for identity and pride had taken a nationalist turn. Flight jackets, T-shirts, and tattoos were proudly emblazoned with Union Jacks. As skinhead gangs congregated at matches, their aggression and militantly nationalistic style truly set them apart.

The rise of skinhead culture mirrored the bleak economic realities of late 70s Britain. With unemployment soaring and punk rock thundering through the airwaves, young working-class men embraced a stripped-back, no-nonsense style that rejected the glamour of the previous decade.

Football’s turn to skinhead uniformity was paradoxical: in the crowd’s sameness lay its strength. Uniformity wasn’t a denial of self but a foundation of identity. By blending into the group, individuals drew power to stand apart. Skinheads on the terraces—shaven-headed, booted, and ready for confrontation—were a collective like no other, united by class, anger, and a shared sense of alienation. They weren’t apologetic for being British; they wanted their country back from those who were.

Skinhead fashion was more than style—it was a language. Flight jackets, Crombie overcoats, slim-cut Levi’s, and Fred Perry polos were markers of identity, instantly recognizable and loaded with meaning. But the boots spoke loudest. Doc Martens stomped out a rhythm of protest against a backdrop of Oi! music. Whether marching to the pub or onto the terraces, the skinheads were always ready for confrontation—against rival fans, communist agitators, or the establishment itself.

At its core, the skinhead revival was another rejection of excess. It was a counterpoint to the glamour of the 70s, replacing frivolity with practicality and toughness. The terraces became battlegrounds for more than football; they were staging grounds for class tensions, where the skinheads signaled both their place in the world and their resistance to it.

In Thatcherite Britain, where industrial decline and political strife loomed large, skinheads stood as a visual embodiment of disenfranchised youth. On the terraces, they formed a wall of solidarity that echoed far beyond the pitch. Football was no longer just a game. What began as a British working-class movement would grow to became a global export, spawning copycat subcultures among disaffected white youth across the Western world.

Oi! | An aggressive soundtrack

Emerging in the late 1970s, Oi! music became the most aggressive grassroots movement on the British music scene. With its loud, confrontational lyrics, Oi! expressed working-class anger and disillusionment. Bands like Skrewdriver, Skullhead, and Condemned 84 were notorious not only for their raw sound but also for their controversial associations. Connected with the Rock Against Communism movement, Oi! came under fire for its provocative stance and sometimes incendiary messages, which led to repeated cancellations of Oi! concerts across Britain and a refusal by easily-offended middle-class music journalists to recognise this musical movement. Despite this, less controversial bands like Sham 69, Cockney Rejects, and Angelic Upstarts brought the Oi! sound to mainstream attention. Sham 69’s chant-friendly tracks like Rip Off and If the Kids Are United became rallying cries, while Cockney Rejects' War on the Terraces and Angelic Upstarts' Blood on the Terraces offered a grim yet defiant portrayal of the violence and camaraderie of football culture in England. Oi! was like an Anglo-Saxon battle cry—a soundtrack that embodied the defiant working-class energy of the skinhead movement and remains both legendary and contentious in British subculture history.

Turning casual

As the 1980s dawned, the terraces underwent another transformation. The brute-force aesthetics of the skinheads gave way to something more covert, though no less defiant. Enter the casuals—a subculture defined not by laid-back attitudes but by their embrace of designer sportswear.

This shift was more than a style evolution; it was a calculated response to increasing police surveillance and crackdowns on hooliganism. The skinhead look had become too obvious, too easy a target. Casual fashion offered camouflage, allowing fans to blend in, move freely, and avoid the immediate suspicion of the Old Bill. Born of necessity and taste, the casuals’ understated style was both practical and aspirational, enabling supporters to fly under the radar while cultivating an exclusive, status-driven look.

Unlike the skinheads, who wore their defiance on their sleeves (and in their boots), the casuals opted for subtlety. Their sartorial choices were a kind of code—Burberry scarves, Aquascutum golf jackets, Pringle sweaters, Ellesse and Sergio Tacchini tracksuit tops, Lacoste polos, Farah slacks, and Fila trainers formed a uniform only the initiated could recognize. Even tweed jackets and gold-buttoned blazers occasionally crept in, adding a nod of sophistication to the subculture.

By the mid-1980s, Stone Island had begun to appear at England away games, though its story as a terrace staple would truly take hold in the 1990s.

The casual aesthetic was aspirational. Against the backdrop of Britain’s industrial decline and rising unemployment, young working-class fans found inspiration in continental away days, returning with a wardrobe that redefined football culture. The casuals were fluent in the semiotics of fashion, embodying Roland Barthes’ idea that clothing is an abstract system of signs. Every item was a statement, a coded message about class, taste, and belonging. Needless to say, the authorities would eventually learn how to spot the camouflage and read the signs. And so would the fashion press. Casual style would come to influence the wider culture and the way people dress to this day.

But beneath the veneer of sophistication, the casuals carried an edge that distinguished them from the merely clothes-obsessed. Football violence remained central to the subculture, yet the casuals preferred to outsmart their opponents. Dressed like golfers in pastels, they could infiltrate rival territories undetected by police or opposing fans. This was football’s version of guerrilla warfare. Where the skinhead might wield a knuckle duster, the casual carried a Fox umbrella—elegance doubling as a weapon. This obsession with designer labels, mirrored the rise of consumer culture in Thatcherite Britain. Yet the embrace of exclusivity was less about materialism and more about reclaiming status.

By the late 1980s, the casuals had cemented themselves as a dominant force on the terraces. But their hunger for distinction was insatiable. As Bernard Williams once noted, “We may pass violets looking for roses. We may pass contentment looking for victory”. For the casuals, every outfit was a battle won, every Saturday a step closer to the elusive victory of being the best-dressed man in the crowd.

Manchester’s influence

As the 1980s drew to a close, football fashion underwent another seismic shift. The sharp, designer-driven aesthetic of the casuals gave way to the euphoric haze of the Madchester scene—originating in Manchester—a cultural phenomenon shaped by football, music, and the rise of ecstasy.

Madchester fused rave culture with indie rock, shaping not just sound but an entire way of life. Football fans, much like the club-goers of the Hacienda, embraced a laid-back, hedonistic aesthetic that mirrored the blissed-out vibe of the era. Baggy clothes replaced the sharp lines of early casuals, with oversized smocks and sweatshirts, baggy jeans, and psychedelic patterns dominating the terraces. The new uniform was as much about practicality as it was about attitude—perfect for a day in the stands and a night on the dancefloor. Bands like The Stone Roses, Happy Mondays, and 808 State didn’t just soundtrack the movement; they borrowed from and fed back into terrace culture, creating a feedback loop of music and style.

The arrival of ecstasy altered football fandom in unexpected ways. Once defined by tribal aggression, the terraces took on a more euphoric, less confrontational atmosphere. The fan on ecstasy was more likely to spark a chant than a brawl, turning matches into an extension of the rave. This newfound sense of freedom and community was reflected in the era’s baggy fashion—looser, more relaxed, a reflection of the mad-for-it attitude that defined late-‘80s Manchester. This fashion reflected the contradictions of the time. Fans were lost in the escapism of music and raves in the face of the looming Premier League era, as football stadiums grew more sanitized and clubs became increasingly corporate and boring.

The authorities, gripped by a moral panic over rave culture, cracked down hard, targeting illegal raves and stifling the unity born of the scene. Their heavy-handed approach inadvertently sobered up many former revelers, some of whom returned to old habits. The state was the enemy once more. As the music dimmed and the ecstasy wore off, violence and tribalism once again found their way back to the terraces.

No face, no case

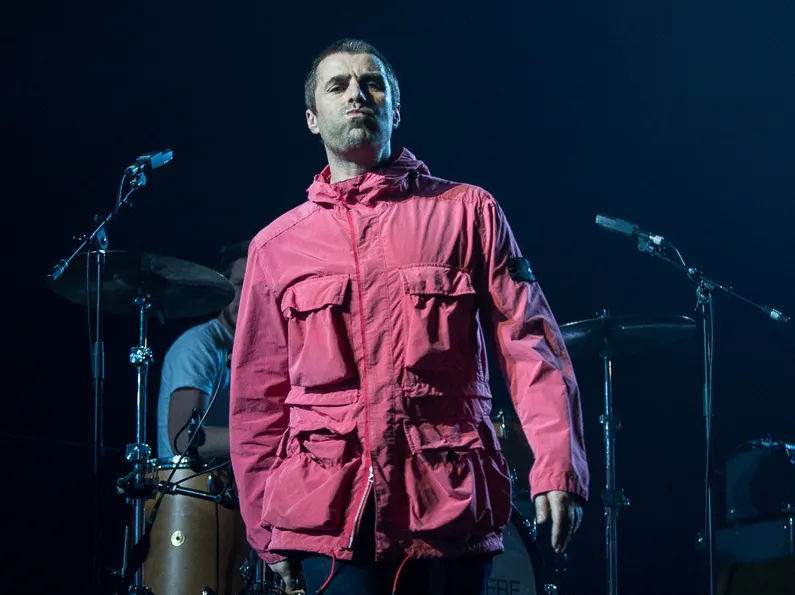

As the 2000s unfolded, football fashion continued to evolve, yet echoes of past eras lingered. Britpop bands like Oasis championed a distinctly British hooligan swagger, mirroring the pride and belligerence that had long defined football culture.

Morrissey’s 1992 album Your Arsenal captured this complex relationship. In “We’ll Let You Know,” he sang, “Then, honest, I swear, it’s the turnstiles that make us hostile,” encapsulating the tribal loyalty that drove football supporters. His lyrics, “At heart, what’s left, we sadly know / That we are the last truly British people you’ll ever know,” echoed the sentiment of being a dying breed—Hilaire Belloc’s “last of England”. This duality of pride and alienation found a natural home among hooligans.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, hooligans sobered up from their ecstasy haze and reconnected with the aggressive tribalism that defined them. The terraces, once colourful and carefree, shifted toward a sleeker, more tactical aesthetic dominated by the unmistakable compass logo of Stone Island and the militant sensibilities of the black bloc.

Stone Island, founded by Italian designer Massimo Osti, had flirted with football culture since the 1980s but became the defining brand for British football hooligans by the turn of the millennium. The brand’s iconic compass patch became a badge of allegiance. Stone Island’s military-inspired designs and weatherproof fabrics made it ideal for long hours on away days. The Raso Gommato jacket, with its technical fabrics and muted tones, exemplified this shift: a blend of functionality and style, offering both camouflage and a statement of readiness.

This evolution extended to the adoption of covert black bloc styles. Drawing inspiration from anti-globalization protests and revolutionary movements, these outfits shed the loud logos and bright colours of the 1990s, replacing them with monochrome palettes, tactical gear, and minimalist branding. Black became the terrace uniform—not just for its understated cool but for its practicality. In an era of mass surveillance, the “no face, no case” mentality emerged, with anonymity and protection from police scrutiny as essential as solidarity. Items like the CP Company goggle jacket, with lenses embedded in its hood, embodied this duality: obscuring identity while signaling allegiance to the culture.

The black bloc aesthetic represents the culmination of decades of football fashion. It marries the defiance of the skinhead era with the exclusivity of the casuals and the utilitarian pragmatism of Stone Island. Football fashion has been stripped of its exuberance and distilled into something sharper, colder, and more calculated. Helly Hansen, Henri Lloyd, Barbour, Nigel Cabourn, CP Company, and Stone Island remain dominant, their military influences firmly rooted in terrace culture.

Yet, as with earlier eras, the black bloc look is about more than clothes—it’s about politics. Today’s terraces remain a stage for expressing class solidarity and resistance. This pared-back aesthetic reflects a rejection of the commercialization that has transformed football into a multi-billion-pound industry. The modern hooligan dresses not for a party but for a fight, defiant against the gentrification of the sport and the erosion of national identity.

The last of the pirates

In many ways, football hooligans are the last of the pirates—unbound by conventional laws, norms, or even borders. Like roving bands of marauders, they are drawn to the thrill of shared adventure, an exclusive brotherhood defined by loyalty, bravado, and a relentless drive to live on the edge.

When they descend on a city on tour, they bring a palpable energy—equal parts chaos and charisma—that is as much feared as it is, strangely, admired. Whether commandeering pubs and hoisting their flags or charming the local women, they weave their own myths. These are modern-day rebels who move as they please, answering only to each other and the unspoken codes of their tribe.

For all their provocations, hooligans embody a raw, untamed spirit that keeps alive the age-old tales of plunderers and renegades. In a world increasingly constrained by rules and surveillance, they are a reminder of a freer, more vital way of life, leaving their mark wherever the match might take them.