The Weimar Republic, a fragile democracy that governed Germany from 1919 to 1933, occupies a paradoxical place in history. Few periods in modern history have so vividly reflected the heights of human creativity and the depths of human despair.

A shattered beginning

The Weimar Republic emerged from the devastation of the First World War. Germany’s crushing defeat led to the abdication of the Kaiser and the establishment of a precarious democracy in 1919. Humiliated by the Treaty of Versailles, which imposed crippling reparations and stripped the nation of territory, Germany became a country adrift, burdened by resentment and financial ruin.

The war itself had heralded the chaos wrought by modernity, with mechanized slaughter on an unprecedented scale. This upheaval, as Walter Benjamin observed, led to a profound devaluation of experience. For a “generation which from 1914 to 1918 had to experience some of the most monstrous events in the history of the world”, the very notion of shared human experience was shattered, leaving behind a world where tradition and meaning seemed irreparably fractured.

This disillusionment was compounded by the rapid encroachment of modernity in everyday life. Urbanisation, industrialisation, and the rise of mass culture unsettled traditional hierarchies and ways of life. Cities like Berlin became symbols of opportunity and alienation, forcing Germans to reckon with the collapse of the old world and the demands of the new.

Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West (1918) captured the anxieties of the age, articulating a grim vision of impermanence and decay. “The life of the individual—whether this be animal, plant, or man—is as perishable as that of cultures,” Spengler wrote. “Every creation is fore-doomed to decay, every thought, every discovery, every deed to oblivion.” To Spengler, the Republic’s permissiveness and cosmopolitanism were not signs of progress but symptoms of a society in moral and spiritual decline, echoing his broader pessimism about the fate of civilizations. Yet, where Spengler saw only decay, others saw opportunity—a blank slate upon which new art, ideas, and social structures could be inscribed, free from the constraints of a vanishing past.

In this atmosphere, Weimar culture flourished. Germans, caught between despair and hope, chose to live for the moment.

A disenchanted world

Max Weber, the German sociologist, described modernity as a “disenchantment of the world”, a shift from societies rooted in magical or religious thought to ones dominated by rationality, science, and bureaucracy. In his analysis of modernization, Weber identified a loss of the spiritual frameworks that once provided meaning and order.

In Weimar Germany, this disenchantment was profoundly felt. The trauma of the First World War, combined with rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, accelerated the erosion of traditional values. Secularism replaced religious authority, and mysticism gave way to rationality.

Disenchantment did not exist in a vacuum—it carried profound political consequences. With old certainties dismantled, people turned to radical ideologies like fascism and communism, seeking new sources of identity and meaning. Weber himself warned that modernity’s relentless focus on rational systems risked creating an “iron cage”, trapping individuals in a soulless, bureaucratic order devoid of transcendence and beauty. Yet, the secular belief systems that emerged in this disenchanted age—far from liberating humanity—unleashed unprecedented violence, claiming far more lives than the spiritual beliefs they sought to replace.

While some embraced the chaos of modernity, others longed to reclaim the enchantment that seemed irrevocably lost. In Weimar, this tension between rational progress and spiritual emptiness found vivid expression in its art, literature, and nightlife.

Chaos as cultural catalyst

The Weimar era was defined by fluctuations and contradictions. It was an era of extraordinary cultural innovation, shadowed by profound political instability, economic collapse, and social upheaval.

The hyperinflation of the early 1920s saw the German mark become almost worthless, with workers paid twice a day to keep up with rising prices. Yet, even as the economy crumbled, Berlin became the epicentre of a cultural renaissance. People often spent their earnings immediately on entertainment and nightlife, fueling a sense of spontaneity and hedonism in the arts. Cabarets, jazz clubs, and avant-garde performances thrived as people sought escape and distraction from economic hardships.

“The romanticism of the underworld betwitched me. I was magnetized by the scum. Berlin-the Berlin I perceived or imagined was gorgeously corrupt.” ~ Klaus Mann

The mid-1920s, often referred to as the “Golden Age” of Weimar, saw relative economic stability and growth. This period was marked by a flourishing cultural scene, with increased investment in the arts and a more optimistic outlook. Creativity blossomed as artists, writers, and filmmakers had more resources and opportunities to experiment and innovate.

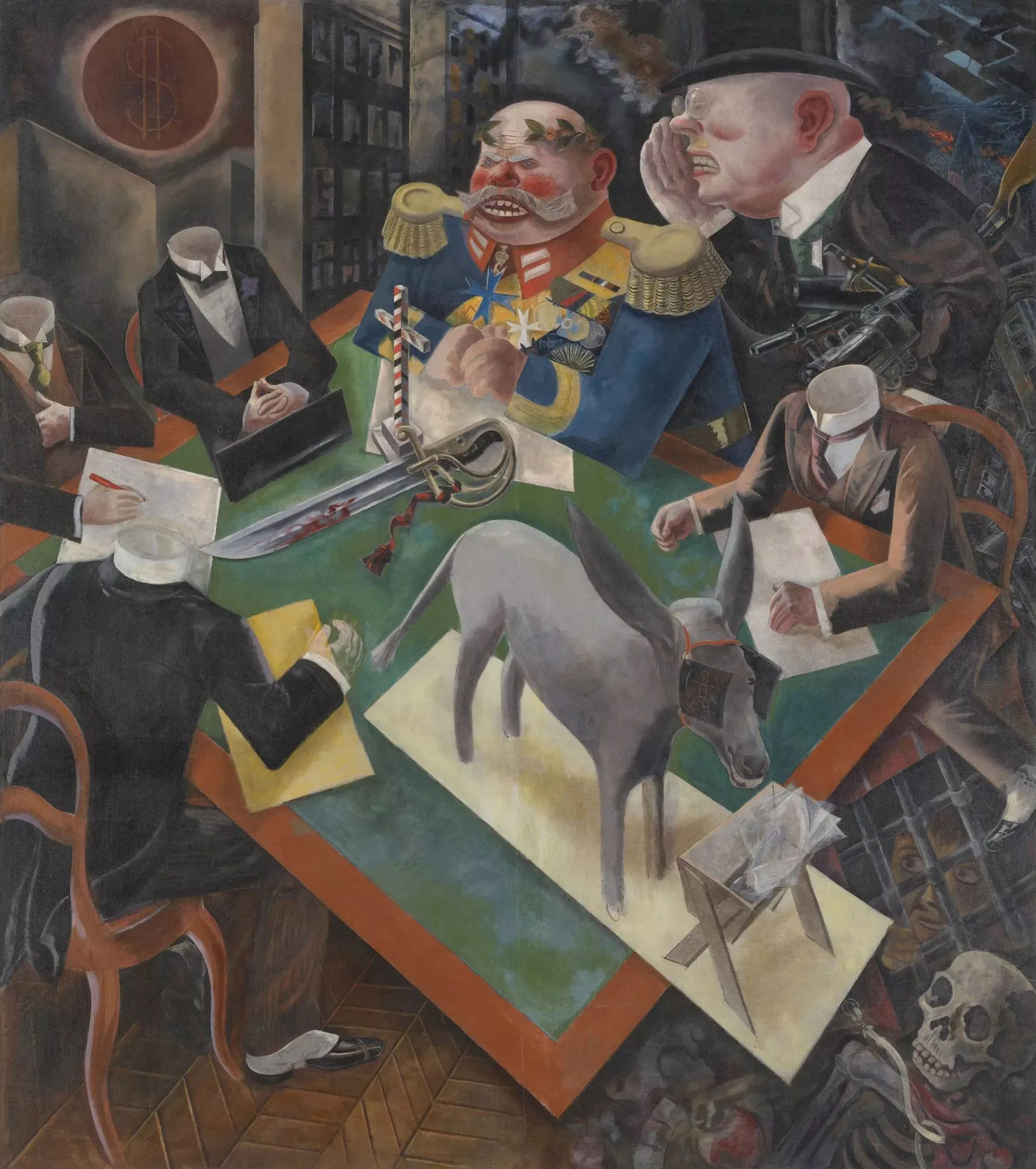

Expressionism, already prominent before the war, found new urgency in the postwar years. Painters like Otto Dix and George Grosz turned their gaze to the grotesque, portraying a fractured society in garish, unflinching detail. The scars of the First World War ran deep—veterans returned home physically and psychologically shattered, their suffering immortalized in Dix’s grotesque depictions of war victims and Grosz’s scathing caricatures of the bourgeoisie.

“Art is exorcism”, Dix famously declared—suggesting that, through art, Germany could confront and transmute the horrors of war and the despair of modern life.

Meanwhile, the Bauhaus movement, led by Walter Gropius, sought not only to innovate but to heal. Gropius and his colleagues envisioned a utopian ideal of art, technology, and society combined. The Bauhaus redefined architecture and design, marrying art with industrial functionality in a way that embodied a rational, forward-looking spirit.

Art Deco, with its elegance and geometric precision, also flourished during this time, blending modernity with opulence. This aesthetic movement, evident in everything from fashion to architecture, symbolized the glamour of the age.

German expressionist cinema reached its peak during this period, exploring the psychological depth of alienation, ambition, and moral decay. Films such as Fritz Lang’s M and Metropolis, and F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, used shadow and symbolism to reflect the anxieties of the age. Meanwhile, in the theatre, Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill pioneered an explicitly political art form. Their collaborations, including The Threepenny Opera (1928), fused satire, jazz-infused music, and social critique.

This was also the age of the “New Woman”, epitomized by actresses like Marlene Dietrich and Louise Brooks. With women granted the vote in 1919, new possibilities opened up, and many embraced a freer, more independent way of life. The “New Woman” was sexually liberated, financially self-sufficient, and fashionably androgynous. Cropped hair, menswear-inspired tailoring, and a cigarette in hand became the trademark of the New Woman. Dietrich’s performance in The Blue Angel (1930) and Brooks’ performance in Pandora’s Box (1929) embodied this movement, portraying women who wielded their sexuality with confidence.

Sexual revolutionaries

Berlin in the Weimar era became the epicentre of a sexual revolution that continues to shock and fascinate. As Mel Gordon recounts in Voluptuous Panic, every form of sexual expression found its place in the city’s nightlife. Berlin radiated an atmosphere of sexual experimentation and abandon.

Prostitution surged, driven by hyperinflation and widespread unemployment, as women, men, and even children turned to sex work out of economic necessity. Amid this upheaval, Berlin became a haven of liberation for those constrained by the moral strictures of their own societies. Cabarets, brothels, and nightclubs catered to every imaginable taste, fostering a permissive culture unmatched in its time. Same-sex relationships, cross-dressing, and open relationships were celebrated, and Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Science), founded in 1919, campaigned for gay and transgender rights while performing some of the world’s first transgender surgeries. For British writer Christopher Isherwood, who had grown up under the rigid moral code of England, Berlin offered a freedom he had never known. Living there in the 1920s, his experiences in Berlin’s demi-monde inspired his Berlin Stories, later adapted into the musical Cabaret.

Berlin’s libertine culture inspired a creative explosion in literature, art, and performance, yet it also provoked a fierce backlash. For conservatives, the city’s permissiveness became a symbol of moral decline and societal decay. Berlin laid bare the contradictions of the era—poverty on the margins, indulgence at the centre, and an underlying sense of desperation. These tensions foreshadowed the rise of reactionary forces, as Weimar’s permissive culture would ultimately become a target for the conservative and nationalist movements that sought to dismantle it.

Nightlife

Weimar Berlin’s nightlife was legendary, serving as both an escape from economic and political turmoil and a hub for cultural and social experimentation. At its peak, the city had over 500 nightclubs, catering to everyone from the bourgeois elite to the criminal underworld. Cabarets featured jazz, drag performances, and open displays of sexuality. Some venues encouraged sailors’ uniforms, leather outfits, or cross-dressing, while others appealed to more subdued tastes. The boundaries between respectable entertainment and illicit activity often blurred within these venues. Prostitution was a common, informal aspect of Berlin’s nightclubs. In Voluptuous Panic, Mel Gordon vividly captures the scene’s eroticism, highlighting how sexual freedom was not only visible but celebrated in ways unmatched elsewhere in the Western world at the time. The city’s libertine spirit left an indelible mark on visitors. W.H. Auden, who spent time in Berlin during this era, is often said to have quipped that the city was “a bugger’s daydream”.

Among Berlin’s nightlife institutions, the Eldorado stood out as a hub for cross-dressing performers. Meanwhile, the Resi (Residenz-Casino) offered an extravagant experience, complete with a massive dance floor for 1,000 people, private telephones for discreet flirting, and pneumatic tubes for sending gifts and messages between tables. Another iconic venue, the Moka Efti, combined opulence with eclecticism: part nightclub, part seafood restaurant, it also featured a billiard hall, a barber shop, and a pastry shop styled like a sleeper train from the Orient Express.

Weimar vs. late Rome | decline or transition?

The parallels between Weimar Berlin and the decline of Rome are frequently drawn. Both periods witnessed profound societal shifts, particularly in attitudes toward sex and gender. In late Rome, chroniclers like Tacitus and Suetonius described decadence, public orgies, and fluid gender roles. Similarly, Weimar Berlin embraced a visible, permissive culture. Suetonius on Nero: "He castrated the boy Sporus and actually tried to make a woman of him; and he married him with all the usual ceremonies, including a dowry and bridal veil." Both eras also faced economic instability: Rome’s rampant inflation and wealth inequality undermined its foundation, just as hyperinflation and economic disparity plagued Weimar Germany. Despite these challenges, both periods were marked by extraordinary cultural achievements. Late Rome gave us advances in architecture, art, and philosophy, while Weimar Germany produced groundbreaking art, film, and music. The comparison, however, has its limits. The Roman Empire’s decline spanned centuries, while Weimar’s collapse was sudden and shaped by external forces, such as the Treaty of Versailles and the Great Depression. Rather than a terminal decline, Weimar Berlin might better be understood as a period of transition—a society caught between the old world and the new, grappling with modernity’s upheavals.

Radical thinking

Weimar Germany was a fertile ground for experimentation, where nearly every norm—sexual, cultural, and political—was questioned, upended, or reinvented. From subcultures to radical political thought, Berlin became a laboratory of social transformation.

Intellectuals, like the culture around them, were in revolt against the status quo. Ernst Bloch’s The Spirit of Utopia (1918) envisioned the possibility of a better world, even amidst despair. Meanwhile, Carl Schmitt argued that liberal democracy was doomed by its own contradictions, laying the groundwork for authoritarian alternatives. The intellectual landscape was a battleground of competing visions for Germany’s future—utopian, reactionary, and everything in between.

These debates were not abstract; they played out in the everyday lives of Berliners. The Freikörperkultur (Free Body Culture) movement flourished, championing nudism as a path to physical and spiritual well-being. For its adherents, nudity was not merely about exposure but about stripping away the artifice and repression of bourgeois society. Naturist camps and clubs sprang up across Germany, advocating for a return to nature and a rejection of the alienation of the industrial age.

Another subculture that thrived in Weimar Berlin was the so-called “Wild Boys” (wild-frei or wild-clique)—working-class youths who embodied a rough, defiant, and homoerotic ethos. Often dressing in a mix of leather, sailor outfits, and Native American-inspired clothes, they rejected bourgeois respectability and embraced a transgressive counter-cultural identity.

Daniel Guérin, the French anarchist and writer, was fascinated by the subversive energy of these groups. In The Brown Plague: Travels in Late Weimar & Early Nazi Germany, he recounts an encounter with a band of Wild Boys on the outskirts of Berlin—a description that seems to blur the line between observation and fantasy. His vivid portrayal reads more like a projection of his own fascination with rebellion and nonconformity than a dispassionate account:

One Sunday on the outskirts of Berlin, we met by chance a strange troupe on the road. Needless to say, neither their short pants, their bare calves, which disappeared under their long wool vests, the bulky and sundry loads swaying on their backs, nor their enormous hiking boots distinguished them from ordinary vagabonds. But they were very much “toughs.” They had the depraved and troubled faces of hoodlums and the most bizarre coverings on their heads: black or gray Chaplinesque bowlers, old women’s hats with the brims turned up in “Amazon” fashion adorned with ostrich plumes and medals, proletarian navigator caps decorated with enormous edelweiss above the visor, handkerchiefs or scarves in screaming colors tied any which way around the neck, bare chests bursting out of open skin vests with broad stripes, arms scored with fantastic or lewd tattoos, ears hung with pendants or enormous rings, leather shorts surmounted by immense triangular belts — also of leather — both daubed with all the colors of the rainbow, esoteric numbers, human profiles, and inscriptions such as Wild- frei (wild and free) or räuber (robber). Around their wrists they wore enormous leather bracelets. In short, they were a bizarre mixture of virility and effeminacy.

Berlin also became a hub for publications catering to diverse groups and special interests. Der Eigene (The Own), the world’s first gay magazine, featured poetry, political essays, and personal ads. Similarly, Die Freundin (The Girlfriend), founded in 1924, was among the first lesbian magazines in the world, offering stories, advice, and community news. On the political front, Die Rote Fahne (The Red Flag), the official newspaper of the Communist Party of Germany, called for proletarian revolution, while Völkischer Beobachter (The People’s Observer), the Nazi Party’s propaganda organ, denounced communist subversion and the decadence of Weimar culture.

Lustmord

Lustmord (“lust murder” or “sex murder”) was a disturbing but pervasive theme in Weimar-era art, literature, and popular culture. It reflected both a fascination with and revulsion toward the psychological and sexual undercurrents of modern life. Weimar society, gripped by fears of rising crime—exacerbated by economic instability and rapid urbanization—found lustmord both titillating and terrifying.

The theme flourished in crime novels, pulp fiction, and sensationalist journalism. Tabloids splashed lurid headlines across their pages, detailing real-life murders with gory illustrations and shocking photographs. Cheaply printed crime novellas (Krimihefte) fed the public’s appetite for stories that combined murder, sexuality, and psychological intrigue. These works appealed to both the working class and intellectuals drawn to the darker undercurrents of modernity.

The lustmord motif was not confined to pulp fiction—it became a dominant theme in high art, particularly among German Expressionists. Otto Dix is perhaps the most infamous artist to explore the subject. His grotesque, unsettling paintings, such as Sex Murder (1922), depict scenes of sexualized violence and mutilation. Yet these images are not merely sensationalist; they are scathing critiques of the moral decay Dix saw in postwar Germany.

The lustmord theme reached its cinematic apex in Fritz Lang’s M (1931). The film follows a child murderer haunting Berlin, played with eerie brilliance by Peter Lorre. Lang’s portrayal of the killer is not a simple condemnation but a deeply psychological study of paranoia, compulsion, and the moral failures of society. M blurred the lines between predator and prey, forcing audiences to confront their own anxieties about crime, justice, and the limits of empathy.

The lustmord aesthetic did not vanish with the fall of the Weimar Republic. Francis Bacon’s postwar paintings carried its themes into a new era, confronting violence, brutality, and existential suffering. His Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953) transforms a figure of authority into a screaming, tormented specter, while his flayed figures and twisted forms echo the grotesque distortions of Dix, exposing the darkest recesses of human experience. Meanwhile, the cultural obsession with sex murder and transgressive violence has only deepened, shifting from the margins into mainstream entertainment. The enduring appeal of the serial killer continues to shape popular culture, from Silence of the Lambs and Zodiac to the booming market for true crime books and documentaries. What once unsettled Weimar audiences as grotesque and perverse has now become a fixture of popular entertainment.

A fragile experiment ends

The stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression dealt a fatal blow to Weimar Germany’s fragile economy. With funding for the arts drying up, many artists and cultural institutions struggled. Conservatives, nationalists, and reactionaries increasingly blamed Weimar’s cultural liberalism for its political and economic instability, portraying its decadence as a symptom of national decline.

By 1930, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) was already reshaping Germany’s cultural landscape. To them, Weimar’s permissiveness was a moral catastrophe. Nightclubs and cabarets were shuttered. Art deemed un-German or degenerate was removed from galleries. Much of the public, wearied by years of political upheaval, welcomed this cultural purge. The grotesque visions of Otto Dix and George Grosz—intended as critiques of violence and moral decay—were instead seen as proof of it. To the Nazis and their supporters, Weimar culture was not an exposé of corruption but its manifestation, a symptom of cultural Bolshevism.

The crackdown was swift. The Eldorado was closed in 1932 and repurposed as a local headquarters for the Sturmabteilung (SA), the Nazi Party’s paramilitary wing. Hirschfeld’s Institut für Sexualwissenschaft was ransacked; its promotional materials on sexuality and gender burned in the streets.

In place of Weimar’s avant-garde experimentation, the Nazis promoted an art that was idealized, monumental, and nationalistic. Sculptors like Arno Breker, Richard Scheibe, Willy Meller, and Adolf Wamper created works that celebrated Germanic and classical themes—grand, muscular figures projecting strength and purity.

Painters such as Werner Peiner, Arthur Kampf, and Adolf Wissel produced works that upheld classical ideals of beauty and rural simplicity.

Music looked to the grandiose traditions of Richard Wagner, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Anton Bruckner, while popular entertainment thrived in the form of dance bands and schlager music, with songs like Lili Marleen.

Cinema, too, became a key battleground. Leni Riefenstahl emerged as the new regime’s most famous filmmaker, directing Triumph of the Will (1934) and Olympia (1938). Her films pioneered groundbreaking cinematic techniques. Riefenstahl’s mastery of mise-en-scène, her innovative use of camera movement, low-angle shots, and telephoto lenses, and her ability to stage large-scale spectacles made her one of the most technically influential filmmakers of the 20th century.

Ultimately, Weimar Germany’s greatest cultural achievements were inseparable from its failures. Its radical creativity could not mask the political instability and social fractures that made it vulnerable to reaction. Yet its legacy endures. The art, cinema, and spirit produced at that time continues to resonate.

Weimar too?

The parallels between Weimar Germany and the contemporary West are striking. Both eras are defined by upheaval, experimentation, and uncertainty—where old norms are challenged, and the future feels precariously balanced. As with Hirschfeld’s work, the mainstreaming of once-fringe sexual practices reflects a rejection of tradition, amplified by the internet’s ability to bring hidden subcultures into the mainstream.

Art, film, and literature today often mirror this fragmentation. Postmodernism, street art, and installations challenge conventional beauty and form, yet much contemporary art feels detached rather than revelatory. The celebration of everyday objects—Tracey Emin’s My Bed, Jeff Koons’ balloon animals—often seems less a critique of banality than a surrender to it. Craft is increasingly dismissed as elitist, replaced by concepts that demand interpretation to justify their existence. Without a shared cultural or spiritual aspiration, much of today’s art feels self-referential, emotionally hollow, or overtly didactic.

At least in Weimar, artistic provocation had urgency. Artists weren’t shocking for the sake of it; they were grappling with forces reshaping their world. Lustmord paintings laid bare the violent undercurrents of society, Metropolis envisioned a mechanized dystopia, and Brecht and Weill used satire to expose political contradictions. There was irony, but also substance—an attempt to wrest meaning from chaos. Today, irony often feels like a reflex rather than a tool. Provocation is an industry in itself, but what does it provoke beyond fleeting outrage?

A pervasive irony defines this moment—where sincerity is passé, and spectacle has replaced discipline. Historically, great art has offered a glimpse of something eternal, something beyond the noise of daily life. But when art becomes a soapbox, where political messaging overrides beauty, craft, or complexity, it risks losing its deeper power. Art has always engaged with politics—Goya’s The Third of May 1808 comes to mind—but it shouldn’t be reduced to a sermon. Amid this landscape, artists still pursue transcendence, mastery, and meaning—you just won’t hear about them.

Yet the pendulum always swings back. The Renaissance followed the chaos of the Middle Ages. Romanticism emerged in response to the cold rationality of the Enlightenment. The nihilism of Dada gave way to movements seeking clarity and purpose. As T. S. Eliot wrote, “Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood.” So too does great art, reaching beyond the immediate to something primal and enduring.

For such a shift to take hold, institutional and patronage support is needed. The commodification of art has prioritized what sells, but history shows that true artistic revolutions flourished when art was valued for its spiritual and cultural worth. When art is reduced to a lecture, it leaves no room for feeling, thought, or imagination. No wonder many today feel alienated in galleries, cinemas, and theatres.

The art world thrives on rebellion. Perhaps the next great rebellion will be against the emptiness of modern Western culture itself.

“If we cannot justify the very concept of the aesthetic, except as ideology, then aesthetic judgement is without philosophical foundation. An ‘ideology’ is adopted for its social or political utility, rather than its truth.” ~ Roger Scruton