It begins with a young man walking out of the Hook of Holland with a rucksack, a blanket, a volume of Horace, and a head full of romantic delusions. The year is 1933. Europe, not yet paved over by low-cost airlines and influencers gurning to camera, lies ahead like a half-remembered poem.

He will walk to Constantinople, or at least try to. He is Patrick Leigh Fermor, and his journey belongs to a different order of travel: slower, stranger, and richer than what we know today.

In his A Time of Gifts, Fermor gives us a portrait of travel as it once was: inconvenient, idiosyncratic, gloriously aimless. This was no “48 hours in Vienna” checklist. He slept in barns and castles, wandered into candlelit monasteries, recited Latin verse on snowy bridges, and held entire conversations with locals whose language he barely understood. And it changed him—not in the performative way people now claim travel “changes” you, but fundamentally, almost invisibly, like weather on stone.

Fermor was not a singular figure. Laurie Lee, Gerald Brenan, and Sir Richard Francis Burton all belonged to that much-diminished type: traveller as witness, participant, and pilgrim.

Compare this with the modern traveller. Armed with a smartphone and an itinerary plagiarised from internet listicles, the 21st-century tourist arrives not to encounter, but to consume. The list must be completed. The pasta must be photographed. The street art must be geotagged. They do not so much go as appear in places already staged for their arrival. Experience has turned to evidence.

From grand tourists to gentlemen vagabonds

Before the gap year or the influencer, there was the Grand Tour: a rite of passage for the 18th-century English gentleman, cavorting across continental Europe to refine his taste, master French, and buy armfuls of Canaletto paintings. It was a form of aristocratic finishing school and aesthetic grounding. The names of hotels and cafés across Europe still reflect this period and its patrons: Hôtel d’Angleterre, Café Anglais, Café Milord, Pension Britannique, reminders of that curious, powdered class of pampered English fops.

And yet, the peruked and periwigged macaroni tourist — all frills and finely tied cravats — eventually gave way to something wilder. If the Grand Tourist was travelling to become polished, Lord Byron was travelling to become undone. Sir Richard Francis Burton, a generation later, transformed this Romantic wandering into something darker and more exacting. By the 20th century, the tone changes again. Patrick Leigh Fermor, Gerald Brenan, and Laurie Lee represent something quieter: the gentleman vagabond, half-drifter, half-scholar, formed in the dwindling shadows of Empire and the last gasps of a classical education.

What united these men? A shared distrust of comfort. An affinity for cultures that weren’t theirs. They certainly weren’t looking for the best croissant in Paris, but the kind of internal reordering that occurs only when you’re lost or alone.

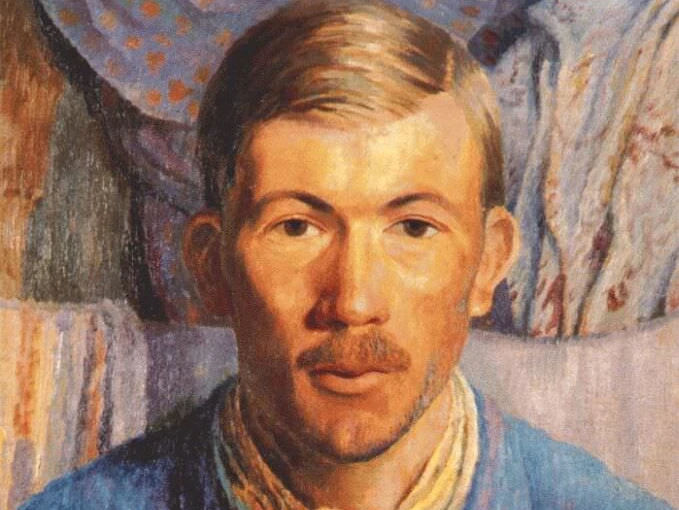

Lord Byron

It is Byron who set the tone: the nobleman turned poet-exile, cutting loose across the Balkans and Levant, indulging in languages, revolutions, and transgression of social norms. Born in 1788 and dead by 36, Byron fled the polite constraints of English society and remade himself on the road. He swam the Hellespont, posed in Albanian dress, wrote verse in Venetian exile, and died fighting for Greek independence. In Greece, he remains something a folk hero.

Byron courted danger and died abroad; the modern traveller demands fast Wi-Fi and leaves bad reviews if the pillows aren’t satisfactory.

Byron travelled not to “see the sights” but to stage a personal transformation. His journey was existential theatre—narcissistic, perhaps, but also deeply committed. And unlike today’s travel-as-performance, Byron’s performance cost him something.

His journeys through the Levant, Albania, and Greece were less about discovery and more about self-reinvention. He seduced and was seduced by the countries he passed through. “If I am a poet,” he said, “the air of Greece made me one.” His was a sensual, myth-soaked travel, driven by appetite and impulse.

Richard Francis Burton

Burton (born 1821) was a polymath, linguist, and iconoclast. A soldier, linguist, explorer, translator of the Kama Sutra and Arabian Nights, Burton took the traveller’s impulse to its limit: infiltrating Mecca in disguise, immersing himself in foreign languages and religions until the line between observer and participant blur. If Byron travelled to feed the soul, Burton released his to the radical Other.

Burton challenged the moralism of his time. Where his Victorian peers sought dominion, Burton sought understanding. He made no claim to belonging to places he visited, but neither did he demand that cultures accommodate him. His reward was a kind of dangerous intimacy with the world, in sharp contrast to the antiseptic, risk-free nature of modern tourism.

Patrick Leigh Fermor

Born in 1915, Fermor was shaped by the last flickers of Edwardian idealism and the Classics. Expelled from school, self-taught, and culturally omnivorous, he walked across 1930s Europe into a gathering storm. His journey was a hymn to European civilisation and a farewell to it.

Fermor walked into places knowing nothing, and left with stories, friendships, whole cultures folded into his memory. The Europe he wandered was variegated and village-minded, a patchwork of dialects, duchies, and deeply rooted customs. Ancient rhythms still held sway. Local memory stretched back to Crusades, to harvest rituals, to grudges held for generations. But the Second World War would bring all that to an end. He fought with the Greek resistance during the war and was ultimately adopted by Greece as one of their own.

Laurie Lee

Born one year before Fermor, Lee was the poet of the road. Where Fermor was studious, Lee was sensuous—less concerned with architecture and history, more attuned to light, food, rhythm. He walked out of Gloucestershire with a violin and a bag of plums, and ended up in pre-war Spain, soaking up its passion and lyricism alike. Lee’s Spanish was negligible, but his ear for tone, gesture, and human detail gave him access that Google Translate never could. Spain remembered him not as a tourist, but as a witness.

Gerald Brenan

From an earlier generation (born 1894), Brenan represents a more ascetic model of escape. Leaving behind the grey rituals of English life, he settled in a remote Andalusian village in the 1920s with a trunk of books and no electricity. He wasn’t there to observe Spain from the outside. He wanted to be invited in. The locals found him strangely English, then tolerable, then familiar. His memoir South from Granada is not a story of travel, but of patient immersion as a kind of intellectual monasticism conducted under the Andalusian sun. Spain gave him solitude; he gave it decades of attention.

These men travelled with reverence, not entitlement. Their presence in foreign lands was not justified by a booking confirmation or a blue tick, but by the seriousness of their attention and the humility of their approach. They weren’t always welcomed, weren’t always right, but they didn’t turn places into backdrops. They let those places press back.

In the decades that followed the Second World War, a new order emerged, rational and technocratic. The post-war consensus sought peace through integration. A universalist, liberal worldview took root across the West. In the rush to modernise, Europe abandoned place-specific ways of being. The sacred, the seasonal, the untranslatable; that which could not be easily explained, or booked online. What had once been a continent of pronounced idiosyncrasies would become increasingly culturally homogenous and ethnically atomised. Europe became more connected and increasingly indistinct.

Where to start | A traveller’s reading list

Lord Byron – Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage

Not a guidebook but a poetic confession in motion. Byron’s semi-autobiographical verses wander across war-scarred Europe, mingling melancholy with landscape, ruin with exaltation.

Patrick Leigh Fermor – A Time of Gifts

The gold standard. This book follows young Fermor on foot from the Hook of Holland to Hungary just before the Second World War. Baroque ceilings, Latin verse, aristocrats in crumbling schlosses. It’s a _Bildungsroman_ disguised as a travelogue.

Laurie Lee – As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning

A lyrical walk from the Cotswolds to civil war–era Spain. Lee writes with sun-dappled clarity and quiet emotional weight. Less about destinations, more about drift, light, and listening. A beautiful meditation on travel as self-discovery.

Gerald Brenan – South from Granada

An English exile’s slow absorption into Andalusian village life. No plot, just perception. Long, thoughtful passages on solitude, culture, and the slow burn of understanding a place from the inside. Walk-on characters include Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf, and assorted apes of god.

Richard Francis Burton – Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah

An astonishing account of Burton’s secret journey into Islam’s holiest city. Expect ethnographic precision, linguistic brilliance, and the experiences of a man who travelled not to observe from a distance, but to let the world remake him in its image.

The tyranny of the list

Travel was once about the discovery of strangeness. Now it is about the confirmation of expectation. Fermor, Lee, and Brenan arrived with no script, no ratings, and little clue. Their journeys were a wager against predictability. They travelled to be surprised, humbled, altered.

When Fermor walked into a Hungarian village, he had no idea what language he’d hear, who might feed him, or whether the next bed would be under a baroque ceiling or in a barn with goats. Lee turned up in rural Spain with the vague hope that someone might exchange food for violoin playing. Brenan moved into the Alpujarras to be left alone with his thoughts and found himself explaining English tea rituals to bemused goat herders.

These were not “experiences” in the modern, marketable sense. They were encounters: awkward and uncurated. Today, the experience is already packaged. You know what Venice is “meant” to be, because a thousand travel blogs and TikToks told you. The photo is pre-posed. The restaurant has a Google rating. The cathedral has a recommended viewing hour. Your job is not to explore, but to execute the plan.

The list, whether printed in a guidebook or loaded into your browser, is the modern traveller’s leash. It ensures that everyone sees the same churches, eats the same pastries, tags the same murals. We are led not by curiosity, but by consensus.

The result is homogenised experience, the same motions performed in a hundred variations by a million interchangeable tourists.

In Venice, you can barely budge in St Mark’s Square. But walk ten minutes in any direction and the canals are yours. The road less travelled isn’t metaphorical—it’s literally just around the corner. It’s just that no one put it on the list.

This is the quiet tragedy: not that people don’t travel, but that they no longer wander. The destination is chosen, yes—but so is the route, the restaurant, the angle of the photo, the time of sunset, the moment of awe. All of it prescribed. None of it personal.

To travel well is to get it wrong. To miss the train. To ask for directions in the wrong language. To eat in the wrong café and find that it was better than the “Top 10 Must-Try Bistros” list could ever predict.

We do not walk into the unknown. We arrive, already knowing. And we leave, unchanged.

On not knowing where you are

E.M. Forster’s A Room with a View is, at its heart, a manifesto against the tyranny of overdetermined journeys. Miss Bartlett, the novel’s anxious chaperone to the innocent Lucy Honeychurch on her travels through Italy, clings to her Baedeker like a sacred text, mistaking its rigid itineraries for experience itself. But Forster’s Italy is no mere backdrop; it is an agent of chaos, a place where unplanned encounters (a murder in the Piazza della Signoria, a kiss in the Tuscan hills) unravel the guidebook’s illusion of control. The Emersons, father and son, are heretics of this orthodoxy, urging Lucy to trade the Baedeker’s sterile authority for the vulnerability of true discovery. Here, Forster exposes travel’s paradox: we leave home to collect sights, yet the moments that claim us are the ones we could never have plotted.

The philosophical school of phenomenology, from Husserl to Merleau-Ponty, rests on one radical idea: the world must be encountered as it appears, not as it is explained. Travel, properly undertaken, is a phenomenological act. You relinquish categories and arrive with subjective awareness and a readiness to be altered by the encounter. This is the opposite of research-based travel. It is the opposite of algorithm-led expectation.

The modern tourist often arrives already defended against experience: armed with reviews, filtered images, travel insurance, local SIM cards, dinner reservations. There is no room for the shock of presence.

It is, in the end, a kind of Socratic move: The only way to truly learn is to be willing to unlearn. To let go of what you think you know about a country, a people, and let new forms of knowing arise.

Even Nietzsche, that great lover of mountains and solitary paths, urged a revaluation of all values: a radical reassessment of what we consider important, meaningful, or worth doing. Travel, at its best, is precisely that. It exposes our assumptions and inherited tastes, and demands that we begin again.

Resisting the itinerary

“The traveller sees what he sees. The tourist sees what he has come to see.” — G. K. Chesterton

The modern traveller does not leave home in search of the unknown, but in pursuit of proof that they have not wasted their annual leave. The itinerary is their talisman. Without it, they fear drifting. But drifting is precisely the point.

Itineraries were once a tool. They are now a theology. Every minute accounted for, every museum pre-booked, every restaurant pre-reviewed, every sunset pre-positioned for optimum lighting. We no longer travel through places but optimise them.

And yet, when one asks travellers what they remember most vividly, it is rarely the planned moments that linger. It is the missed train, the accidental detour, the odd conversation in a doorway. Maybe there was some danger or fear of the unknown that’s makes it all the more memorable.

The fantasy of the perfect trip, pre-choreographed and frictionless, often leads to existential disappointment. Because the world is not frictionless. The best travel is not found in executing the plan, but in surrendering to the real, unpredictable texture of a place.

It is telling that the old travel writers rarely mention itineraries at all. Fermor meanders. Lee wanders. Brenan disappears into the hills. They did not maximise their time, but wasted it magnificently.

In a world obsessed with control, relinquishing the plan and putting down the mobile phone is a grand act of autonomy. The final freedom: to be unapologetically lost.