Byronic once meant living as though one’s life were an epic poem: proud, moody, and unrepentantly dramatic. The figure was tragic yet magnetic, a hero who carried his own storm. The poet endures, but the meaning has changed. Today Byronic circulates as a Nietzschean meme, a gym bro influencer flexing in the mirror of Instagram.

Based Byron begins with Rousseau’s sentimental self and finds its tragic apotheosis in Byron’s heroes — those beautiful failures who sought meaning in a godless world. From there the line runs to Nietzsche, whose Übermensch owes less to Greek statuary than to Manfred, brooding on his Alpine heights. It passes through the European nationalists who painted their revolutions in tricolour, and arrives at today’s men who cultivate strength and solitude as a defence against the flattening spirit of the age — heirs to grandeur, reduced to posture.

The birth of the romantic rebel

The modern cult of the self begins with a confession. In the 1760s, Jean-Jacques Rousseau sat down to write the first great autobiography of the modern age — The Confessions — a work that scandalised his contemporaries. It starts with a trumpet blast: “Myself alone! I know the feelings of my heart, and I know men. I am not made like any of those I have seen… If I am not better, at least I am different.” With that line, Rousseau declared the private soul sovereign. The inward man, once a concern for priests, now claimed the right to stand before the world and speak in the first person singular.

He gave the rebel a worldview: “I worship freedom; I abhor restraint, trouble, dependence.” It is not the language of political theory. The Enlightenment had reasoned about liberty; Rousseau made it a matter of the soul. In that turn lies the heart of Romanticism.

For Rousseau, solitude was not a burden but a blessing. “When alone, I have never known what it is to feel weary; my imagination fills up every void, and is alone sufficient to occupy me.” Here we see the scaffolding of the modern mind: where imagination replaces revelation and rebellion represents authenticity. The solitary walker becomes a prophet of self‑sufficiency, finding in himself both subject and saviour.

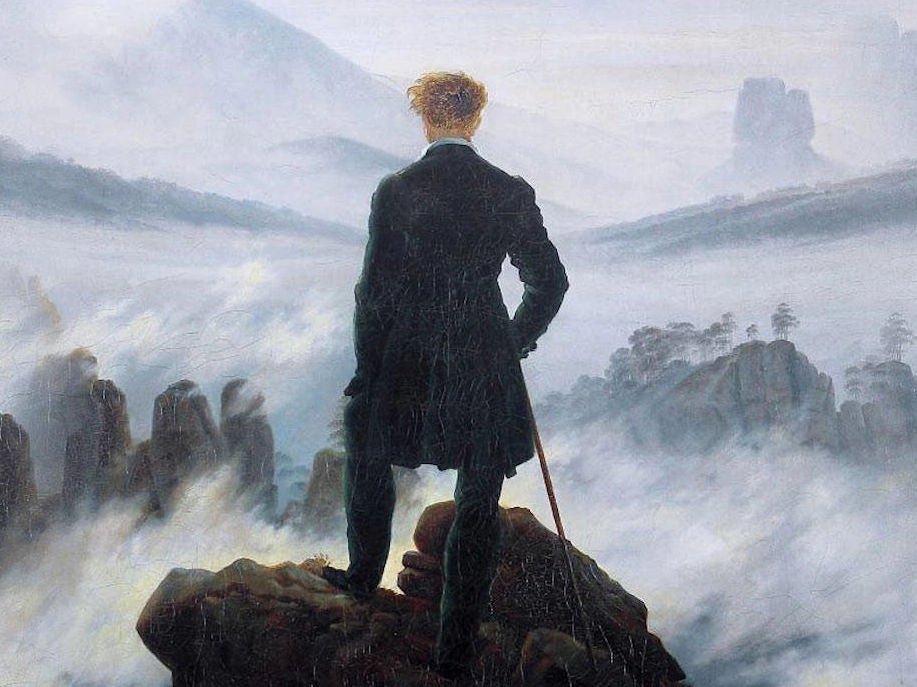

Friedrich’s Wanderer has become a cliché in the age of digital reproduction, but clichés are only truths worn thin by admiration. The solitary figure above the mist in the mountains still captures the Romantic ideal of the self in contemplative exile.

The Confessions, completed in 1769 and published posthumously in 1782, appeared on the eve of the French Revolution. Its pages glowed with the restless energy of a man who could neither obey nor belong. “This reading,” Rousseau recalled of his youth, “formed in me the free and republican spirit, the proud and indomitable character unable to endure slavery or servitude.” Out of this alienation came an entire century of insurrection.

And, finally, Rousseau bequeathed to his heirs a principle that Byron would live and die by: “It is too difficult to think nobly, when one thinks only in order to live.” Dependence kills genius; necessity is the enemy of nobility. It is the principle of every aristocrat of the soul. Byron found in Rousseau the original gesture of protest — inspiring Evola’s differentiated man, standing in contrast against the unthinking herd.

The cultured thug

He was “mad, bad and dangerous to know”. Lady Caroline Lamb meant it as a warning, but we now read it as an invitation. Byron’s infamy outlived his verse, his vices, and even his century, because he made personality itself into an art form.

If Rousseau imagined the unburdened soul before it was corrupted by society, Byron gave it an archetype. He was the Romantic ideal made flesh – intellect sharpened by irony, beauty accentuated with defiance. Born in 1788, on the eve of revolution, Byron embodied the age’s contradictions: aristocrat by birth yet exile by choice, libertine in life yet dedicated partisan in cause.

From the moment Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage appeared in 1812 – and Byron awoke to find himself famous – the poet replaced the philosopher as Europe’s conscience. The young lord wrote of wandering “through many climes and lands remote”. His travels in the Levant and the ruins of Greece made him both participant and chronicler of Europe’s turmoil. The Napoleonic wars had left a generation of men longing to live larger than the age permitted. Byron gave them a model.

He was, as one contemporary called him, “the Napoleon of verse”. Like Bonaparte, he united thought and will. Jonathan Bowden’s quote: “Truthfully, in this age those with intellect have no courage and those with some modicum of physical courage have no intellect. If things are to alter during the next fifty years then we must re-embrace Byron’s ideal: the cultured thug.” – captures this synthesis precisely. Byron’s genius lay in bridging the mind and the body, turning an aesthetic sensibility into action. One can imagine that he fenced as elegantly as he wrote; and that he rode, swam, seduced and argued with the same lyric intensity.

His rebellion was not merely political but metaphysical. In Manfred (1817), written after his exile from England, the hero defies both God and meaning, seeking annihilation rather than repentance. Milton’s “mind is its own place” becomes, in Byron’s hands, a romantic credo. “The mind which is immortal makes itself requital for its good or evil thoughts” is a line Nietzsche could have underlined.

Byron’s death in 1824, in Missolonghi, attempting to liberate Greece from Ottoman rule, completed the myth. The man who had written of liberty died fighting for it in true Romantic style. Where Rousseau turned inward and made the heart his republic, Byron turned outward. In him, the sentimental age of introspection hardened into something more heroic.

Nietzsche carried the arc further. Where Rousseau sanctified feeling and Byron turned rebellion into legend, Nietzsche made the will itself sovereign. In Nietzsche’s hands, the mind is its own law, demanding not consolation or myth but the creation of values. In him, Romantic inwardness hardened into a philosophy of strength.

Byron and Nietzsche

Byronism fuses the intellect’s disdain with the body’s appetite, the poet’s melancholy with the soldier’s daring. In that sense he is the bridge between Rousseau’s solitary dreamer and Nietzsche’s Übermensch.

Nietzsche read Byron with something close to envy. Among the piles of Greek fragments and Schopenhauerian notes in his Basel study, he kept English verse close to hand, and referred more than once to “the Byronic ideal” – a spirit proud and solitary. The philosopher recognised in Byron a prototype of his own higher man: one who lives dangerously, creates his own values, and stands serenely apart from the herd. In Manfred he found, long before Zarathustra, a character that would rather perish than submit.

Byron’s hero is already half-Nietzschean. He rejects divine judgement, exalts will over repentance, and converts suffering into style. “One must still have chaos in oneself to give birth to a dancing star”, Nietzsche wrote – a line Byron actually lived.

Both men were scorned by their age precisely because they rose above it. “The higher we soar”, Nietzsche observed, “the smaller we appear to those who cannot fly.” Byron knew that shrinking gaze all too well; it is the fate of every man who lives by his own law to be mistaken for a madman. Or, as Nietzsche put it, “Those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.”

Each understood life as a work to be shaped, not endured. “I teach you the Übermensch”, Nietzsche declared, “Man is something that shall be overcome”. The Romantic hero thus becomes a metaphysical principle. Emotion distilled into will, rebellion into affirmation, man into myth.

From Byronism to nationalism

Byron died, appropriately, for an idea. In 1824, his fevered body gave out in Missolonghi, having exchanged the salons of Europe for the mud of a Greek encampment. His support for Greek independence was no theatrical caprice but the culmination of a long-standing philhellenism, rooted in his classical education. The Greek War of Independence, which began in 1821, had become the great Romantic cause of the age. Byron arrived not as a poet playing soldier but as a man determined to lend his fortune, his prestige and, if required, his life to the uprising. When he died, the Romantic movement found its martyr, and his image was carried like a relic across a continent already primed for revolution. Newspapers and journals lingered on the pathos of his final days, casting him not merely as a supporter of Greek freedom but as its sacrificial emblem.

The Byronic Hero, the ultimate individualist, subsumed his own destiny into the fate of a nation struggling to be born. This reconciled the Romantic focus on the self with the nationalist focus on the people. Byron saw in the Greek cause a revival of the classical cradle of Western civilization and restoration of the past glory of Athens and Sparta.

Byron played a foundational role in creating the cultural and political environment that made later tricolour and shirt movements possible. He was a lord who championed popular causes. This model was incredibly influential for later nationalist leaders who, while often from educated elites, presented themselves as men of the people, fueled by passion and idealism rather than just cold political strategy. The revolutionary movements that swept Europe in the 1830s and 1840s all drew on Romantic imagery to lend their politics a sense of tragic grandeur. Giuseppe Garibaldi was a fervent admirer of Byron and the Romantic nationalist tradition. He consciously modeled himself on this ideal. The red shirts worn by Garibaldi’s volunteers were not just a military uniform but a powerful symbol, which became a model for later 20th-century mass political movements.

Liberty became not merely a political right but a poetic condition. Even failure carried its own dignity, for the Romantic knew that to fall for an ideal was nobler than to live without one.

Byron’s influence seeped quickly from literature into the visual and musical grammar of nationhood. In Verdi’s Nabucco, the chorus “Va, pensiero” is widely interpreted as a lament for Italy’s lack of unity; in the canvases of Delacroix and Lansac, Greece herself appears as a grieving heroine. Romanticism became the aesthetic of national revival.

Based Byron

The transition from the Byronic hero to the modern meme of self-styled rebellion is a direct, if degraded, lineage. The figure of Byron—or at least a shallow, digitized read of him—is a foundational archetype for a certain kind of online persona. Byron’s life, and his lifelong devotion to sculpting himself as a work of art, reads uncannily like a grand Romantic prelude to looksmaxxing.

BAP’s (Bronze Age Pervert ) entire project is an aesthetic performance. It’s a pastiche of classical statues, Nietzschean aphorisms, and a hyper-stylized vision of vitalism and aristocracy. It’s less a coherent philosophy and more an aesthetic toolkit for building a rebellious, superior self. This is a direct, if radically simplified and ironic, homage to the Byronic project of self-creation.

The figures of the Nietzsche-for-Twitter and podcast right understand that in an attention economy, identity is a brand. Their rebellion, their contempt for the herd, and often outrageous takes are designed to carve out a niche. They are crafting a self as a spectacle to attract their tribe, just as Byron’s cultivated persona attracted readers and admirers across Europe.

The appearance of rebellion is as important, if not more so, than any tangible political action. This is the logical endpoint of the Romantic focus on the individual’s stance against society, stripped of the material stakes Byron ultimately faced. Exiled from English society and dying for the role he was playing, Byron’s performance merged with a tangible, costly reality. What began as Romantic heroism has returned as parody. Byron fought and died for the freedom of Greece; his descendants fight for online engagement. Christopher Lasch saw it coming. In The Culture of Narcissism, he described a civilisation in which the individual, deprived of transcendence, turns himself into a spectacle. What Byron embodied through poetry and adventure, the modern man performs through aesthetics and irony. The narcissist, in Lasch’s terms, doesn’t seek salvation or virtue; he seeks admiration. He transforms his life into a performance for an audience. His relationships become shallow and transactional, serving as a mirror to reflect his own curated image. The mirror has replaced the mountain of Friedrich’s Wanderer.

There is, to be fair, something faintly noble even in this degraded imitation. The gym bro intuits that the self must be made rather than inherited; that strength and beauty are gestures toward transcendence in an age that believes in nothing. The impulse is sound. The gym bro senses what Nietzsche and Byron knew: that to be human is to wrestle with one’s own becoming.

Yet what was once the art of living dangerously has become the art of appearing interesting at that moment. Even so, the impulse endures. The dream of the complete man – strong, beautiful, and free – refuses to die, however many layers of irony we heap upon it. From Rousseau’s noble soul to Byron’s flaming heart to Nietzsche’s dancing star, each age reimagines the same figure: the rebel who would rather die like a lion than live as a sheep. Civilisation may change its manners, but it never loses its appetite for the man who can think like a poet and fight like a soldier. The cultured thug will always be among us.

Byron intuited hyperreality long before it acquired a theory. He treated his life much as he treated his verse, pruning and embellishing until the persona outshone the person. The result was a figure more glamorous and imposing than the man who authored it, and the public, sensibly enough, preferred the copy. His wardrobe, his politics, his adventures, even the hiding of his limp, were cultivated with care. In Byron the myth consumed the man; in our age the myth is all that remains.